“The best moments in reading are when you come across something – a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things – that you’d thought special, particular to you. And here it is, set down by someone else, a person you’ve never met, maybe even someone long dead. And it’s as if a hand has come out, and taken yours.” – Alan Bennett, History Boys.

If you’ve ever set foot in an English department, there is a chance you’ve come across these words. Some of you may have even studied them. I’ve seen them plastered on the walls of a communal space in one school, and heard them poured from the mouths of enthusiastic teachers and lecturers in classrooms and seminars alike. It is a line that captures so perfectly the power of reading and words, and the role they play in forming our own consciousness and sense of self.

There have been claims that reading can alter your humanity and processing since Plato. Through the 1990s and 2010s, people have argued that by empathising with characters we learn to empathise with humans, or that reading literature actually makes you a better citizen. Its impact has been philosophised and psychologised for hundreds of years. So far, research into these claims has come back entirely inconclusive, but the idea that books play a role in developing empathy – the soft skill I think is most important – is one of my great joys in life. You mean one of the ways I might make any of my own hypothetical children kinder would be to read with them? Hell yes, I’m in.

I firmly believe that books help make better people. I also firmly believe they help make better homes.

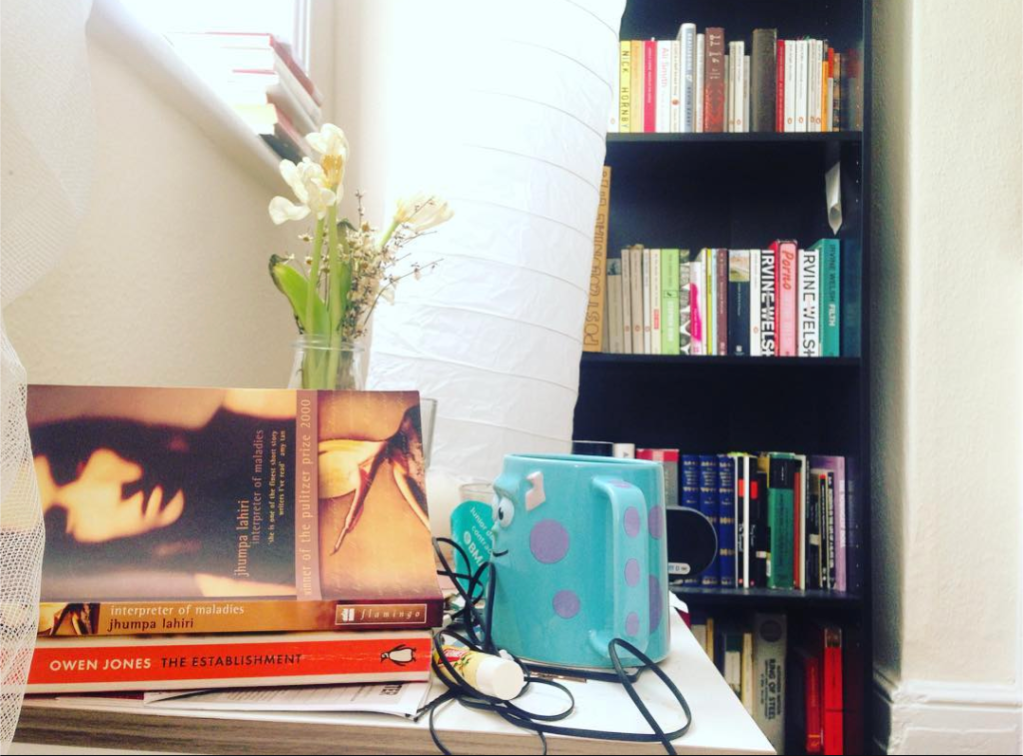

No matter where I’ve lived, my books have been the first means of decorating my space. I spent hours deciding how to order them in university – alphabetically by surname? By colour? In the style of Rob from the 2000 adaptation of High Fidelity, autobiographically? (‘If I want to listen to Landslide by Fleetwood Mac? I have to remember that I bought it for someone in the Fall of 1983 pile, but didn’t give it to them for personal reasons.’) They work on two levels: they give visitors a snapshot into you and your personality, and they add colour into whatever space you are living in. Usually, they are the first thing I look for when I walk into a home, as they give us a foundation for conversation, allowing us to open up big philosophical questions about the world, our relationships, and what it’s all about.

But what happens when their purpose is reduced to little more than decoration? What happens when they become an accessory, and no longer a way of exploring the world from the comfort of your sofa? Are books going the way of fresh food – no longer acting as a symbol of knowledge and inquisitiveness, but more of power and status?

This was something that I first noticed in 2022, when I used to spend every other day watching Architectural Digest’s tours of celebrity homes on youtube. Every house they walk through is artfully staged, and nearly all of them have dominating, wall-to-ceiling bookshelves in jaw-dropping offices. It was Ashley Tisdale who first owned up to the fact that her personal library was not truly reflective of her and her family’s interests, saying ‘These bookshelves, I have to be honest, actually did not have books in them a couple of days ago. I had my husband go to a bookstore and was like “You need to get, like, 400 books!” And my husband was like, “We should be collecting books over time, and like, putting those in the shelves.” But I’m like, not when AD comes!’ Yes, it was funny. Yes, it was refreshingly honest. But there was something about it that jarred in me – as if the purpose of having books wasn’t to encourage curiosity and lose yourself in a thought, but to make your house look interesting.

Then came BookTok, Bookstagram, and other online spaces in which it wasn’t always about celebrating the joy of reading something you like, but being seen reading the book of the moment. From Colleen Hoover and Sarah J. Maas to Sally Rooney and anything published by Fitzcarraldo Editions and their striking blue book covers, choosing a book seemed to be driven by wanting to belong to a group, reflect a trend, and be seen putting the right thing on your shelves.

This is something that anyone who reads has been guilty of, by the way, and has probably existed since learning to read became widespread. I remember reading The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby when I was 16 or 17, not necessarily because I wanted to, but because it’s what all the other cool, indie people in my year who I was friends with and so admired were reading. My obsession with the Brontë sisters only became cool a decade later with the rise of dark academia. And though I read to keep up with my social group, I fell in love with these books and they opened my world up and started my life-long obsession with calling out how destructive capitalism is to our sense of happiness. Although I was reading to keep up with the trends and fashions amongst my peer group, I was shaped by these experiences, and inevitably the next generation of hipsters and indie kids are going through this too – they just don’t have the privilege of doing this without a camera being pointed at them. Reading is reading, and I love to see it!

But performative reading is growing at a time when less young people than ever read for joy, and 18% of adults are functionally illiterate. Reading is amazing and should be celebrated, but when reading is becoming a trend amidst a backdrop of falling literacy rates, it highlights how far we have adopted reading as an aesthetic, instead of a valuable, empathising practice. As beautiful as a well crafted bookshelf can be, if it is filled with books you’ve bought but never opened, or books you’ve swapped for doomscrolling because you weren’t hooked within the first few pages, then what’s the point? You may as well have just visited Ikea and asked for a few boxes of the fake books they use to line the walls of their model rooms and called it a day. Who cares if they’re in Swedish, or are just pages and pages of Lorem Ipsum dummy text? If it’s just for appearances, you’ll achieve the same thing.

All of my biggest fears and issues with performative reading and books as a trend came home to roost earlier this year, when talking to my dad about his home renovations. He told me that he has been reading more, and enjoying it – which is huge, as his attention span is whacked. I don’t remember him being able to sit through reading a chapter of a book with me as a child, instead opting to make up stories about anthropomorphic appliances that kept our house running whilst we slept. He had a vision for a room in the back of his house, which he wanted to fill with books, CDs, and vinyl; a space where you could entertain yourself slowly and without the need of the internet. He followed this up by saying he was just going to get a ‘job lot from eBay’ when it came to filling his shelves.

It was at this point that the knock on effect of the likes of Architectural Digest fully smacked me around the head. My dad could see the role that books played in a house, in creating warmth and personality, but valued their role as decoration over their role as celebrating curiosity.

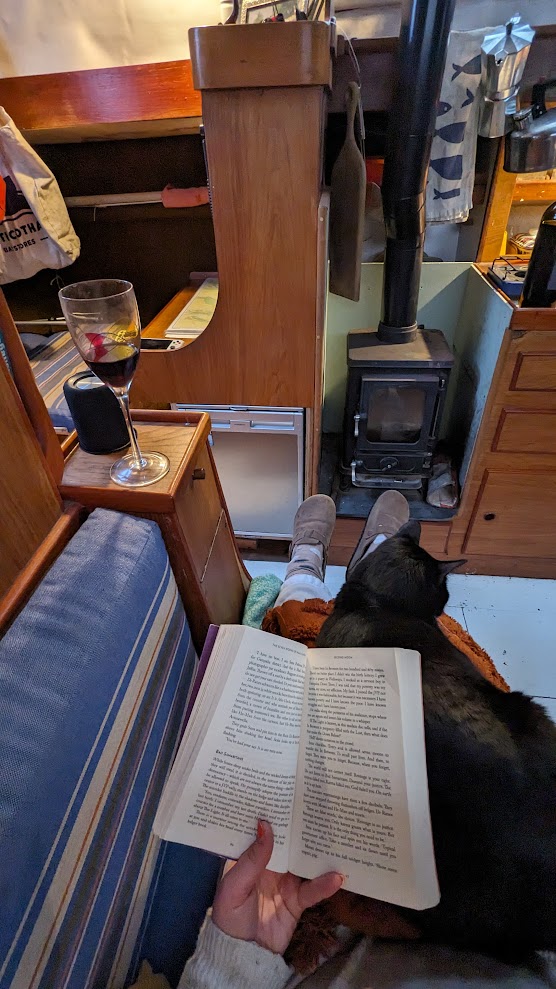

My dad is not a celebrity whose home is going to be on display for millions to nit-pick at. He is a normal man in his fifties, who is excited about a project. But he has adopted a style-over-substance attitude to books from absorbing design magazines and watching house tours on Youtube like I used to. I spoke at him, at length, about the power of books and curating a collection over time; of rummaging through charity shops and swap shops; of lending and sharing books with your community; of crafting a library that might not always look good, but will definitely make you feel whole and full. And the first step I am going to take to help him get there is to send him a parcel of books from my own shelves that I adored, and I think he will too (I will not be posting this, if you’re reading Dad. It will be in the boot of my car next time I come home to visit, promise). There isn’t a better present to give someone than a book you loved off of your shelf – the more dog-ears and notes in the margin the better! In fact, I’m determined to make 2026 the year I pass on more books than ever, if only to make room in our tiny flat and tinier boat for more.

If you are someone, like my own Dad, who wants to start a journey with books, or someone who has a shiny new bookshelf that you want to fill, firstly I envy you. You’re at the start of an adventure that will change you forever. Secondly, please take your time. Every book you add to that shelf – whether it’s a five-star winner, or a DNF (did not finish) – is your chance to discover another part of your personality, and make your heart feel a little fuller. If you’ve got a book that you think belongs on any shelf, comment it below, and help us all shape our 2026 reading lists, and add more life to our living room shelves.

Read slowly, read often, and read to find yourself and others. That’s what a really good book will do for you.